MIT Researchers Unveil Silk-Based Filter to Combat "Forever Chemicals" in Drinking Water

Filter integrates cellulose, producing a membrane highly effective at removing contaminants in lab tests

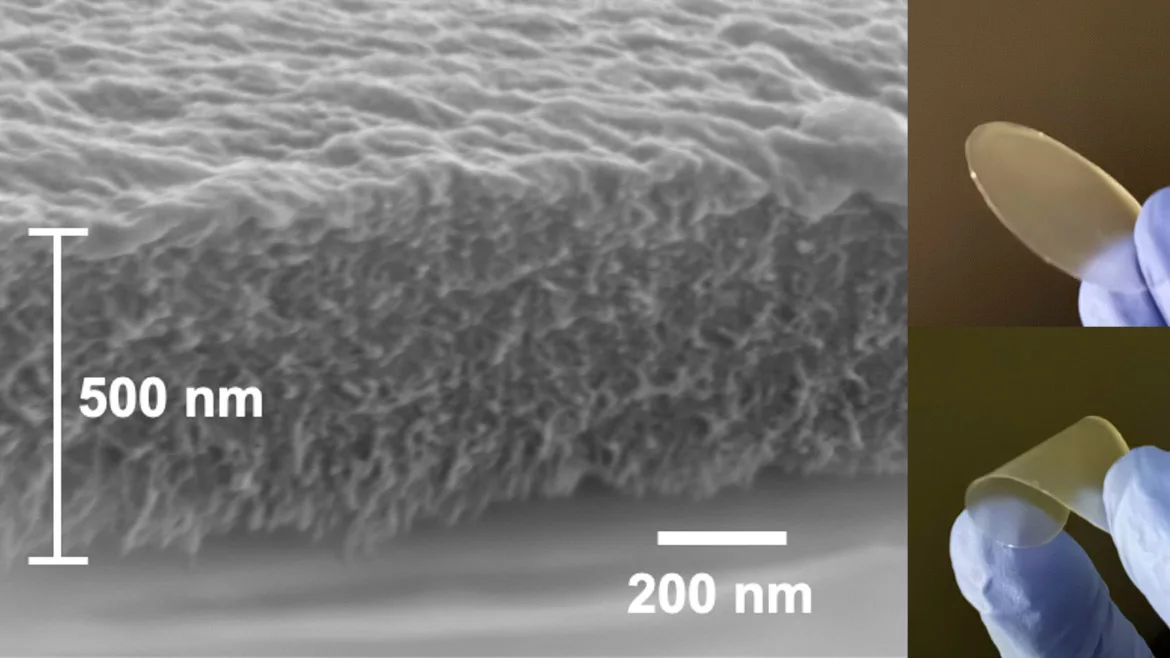

(Courtesy of Yilin Zhang and Benedetto Marelli)

In a breakthrough that could help address the growing problem of water contamination by "forever chemicals," or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), researchers at MIT have developed a new filtration material based on natural silk and cellulose. The innovative filter can remove a wide variety of persistent compounds, known as PFAS, as well as heavy metals, from drinking water. Even more promising, its antimicrobial properties can help prevent the filter from becoming fouled.

PFAS have been found in the bloodstream of 98 percent of people tested, according to a recent study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. These long-lasting chemicals, used in products ranging from cosmetics to firefighting foams, have been identified at 57,000 contamination sites across the U.S. alone. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that remediation will cost $1.5 billion per year to meet new regulations limiting PFAS in drinking water to less than 7 parts per trillion.

"Contamination by PFAS and similar compounds is actually a very big deal, and current solutions may only partially resolve this problem very efficiently or economically," said Yilin Zhang, an MIT postdoc and lead author of the study published in ACS Nano. "That's why we came up with this protein and cellulose-based, fully natural solution."

The filter material was created by integrating cellulose, derived from agricultural wood pulp waste, into silk-based nanofibrils. By tuning the electrical charge of the cellulose, the researchers produced a membrane highly effective at removing contaminants in lab tests. The charge also gave the material strong antimicrobial properties, reducing the risk of filter fouling by bacteria and fungi.

"These materials can really compete with the current standard materials in water filtration when it comes to extracting metal ions and these emerging contaminants, and they can also outperform some of them currently," said Benedetto Marelli, an MIT professor of civil and environmental engineering and senior author of the paper. Lab tests showed the new material can extract orders of magnitude more contaminants from water than commonly used filters like activated carbon.

While the researchers plan to further improve the material's durability and scalability, they envision it initially being used in point-of-use filters attached to kitchen faucets. With both silk and cellulose being food-grade substances, the risk of introducing contamination into the water supply is low.

"Most of the normal materials available today are focusing on one class of contaminants or solving single problems," Zhang noted. "I think we are among the first to address all of these simultaneously."

The work was supported by the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, and the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, and involved an interdisciplinary team of MIT researchers.