Study Reveals 'Forever Chemicals' in Drinking Water Linked to Rare Cancers

Researchers from USC's Keck School of Medicine publish study revealing PFAS contamination may be causing thousands of cancer cases a year

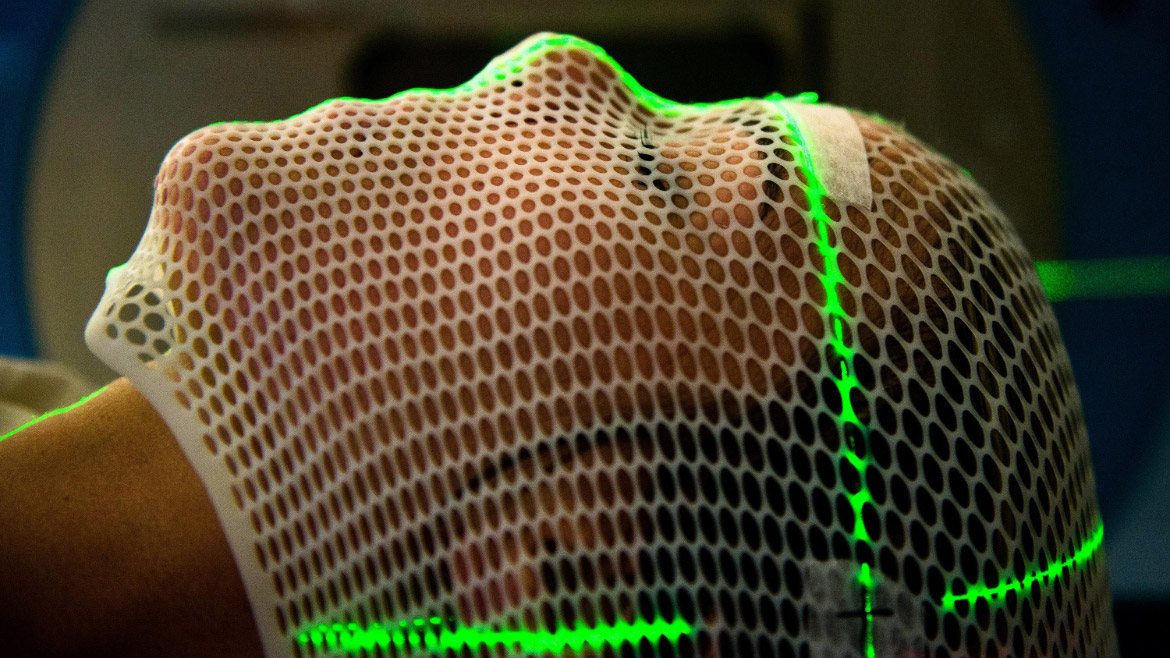

Air Force Capt. Candice Adams Ismirle prepares for radiation therapy. (Courtesy of the U.S. Air Force)

A study from USC's Keck School of Medicine has uncovered a disturbing connection between contaminated drinking water and increased cancer rates across the United States. The research shows that communities exposed to PFAS — synthetic chemicals commonly found in everyday products — face up to 33% higher rates of certain rare cancers.

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, have earned the nickname "forever chemicals" due to their persistence in both the environment and human bodies. These compounds, present in items from furniture to food packaging, have now been detected in approximately 45% of U.S. drinking water supplies.

"These findings allow us to draw an initial conclusion about the link between certain rare cancers and PFAS," said Dr. Shiwen "Sherlock" Li, the study's lead author. "This suggests that it's worth researching each of these links in a more individualized and precise way."

The research, published in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, reveals a stark reality: PFAS contamination may be responsible for more than 6,800 cancer cases annually in the United States. The study examined data from 2016 to 2021, comparing cancer rates in counties with PFAS-contaminated drinking water to those without contamination.

The impact varies by gender. Men in affected areas showed higher rates of leukemia and cancers of the urinary system, brain, and soft tissues. Women experienced increased instances of thyroid cancer and mouth and throat cancers. Overall, researchers found elevated rates of digestive, endocrine, respiratory, and oral cancers in contaminated areas, with some cancer risks increasing by as much as 33%.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) plans to begin regulating six types of PFAS in drinking water by 2029. However, Dr. Li and his colleagues suggest these upcoming regulations might not be sufficient to protect public health. Their findings indicate that even less-studied PFAS compounds may pose significant health risks.

The study's implications extend beyond public health concerns. With thousands of cancer cases potentially attributable to PFAS exposure each year, the financial and personal toll on affected communities could be substantial. The research team controlled for various factors that might influence cancer risk, including age, sex, socioeconomic status, smoking rates, and obesity prevalence, strengthening the connection between PFAS exposure and cancer incidence.

As this research opens new avenues for understanding the health impacts of these ubiquitous chemicals, it also raises urgent questions about current environmental regulations and the steps needed to protect public health in the face of continuing PFAS exposure.

.jpg?height=200&t=1663879182&width=200)