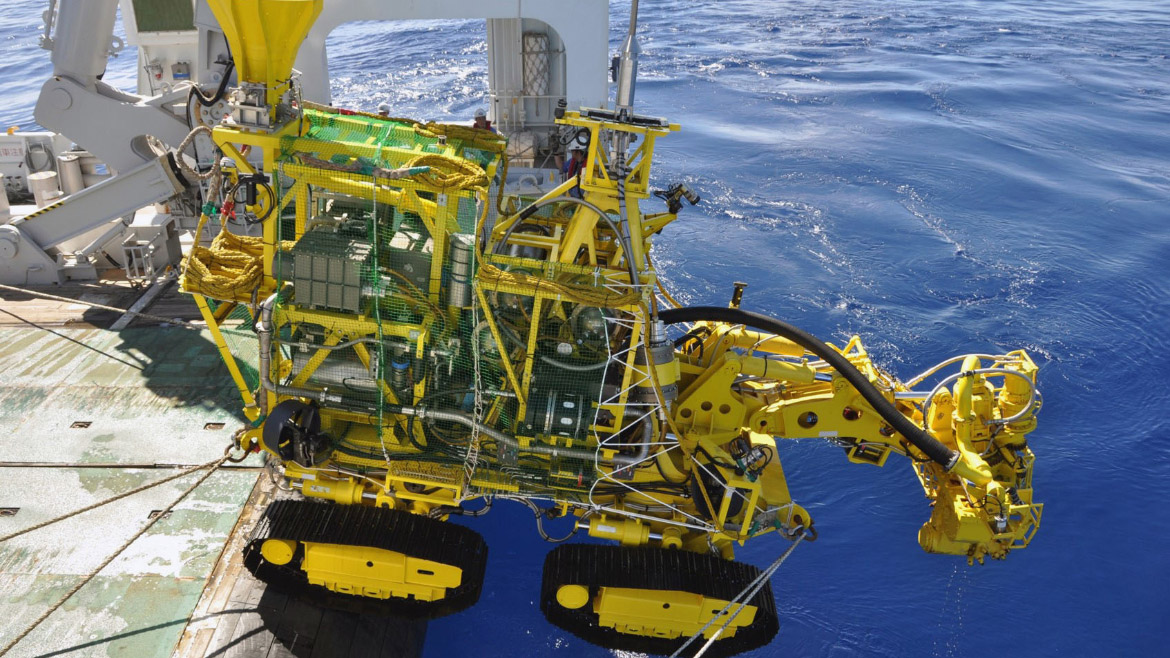

Deep sea mining set to begin commercial production in 2024

The long-delayed polymetallic-nodule mining industry is picking up speed following regulatory victories.

Photo courtesy of Japan's Agency for Natural Resources and Energy

NGOs opposed to deep sea mining have successfully delayed the nascent industry, rallying 13 countries like France and Germany in calling to further delay commercial-scale production in international waters, relying on the power of the 1994 United Nations Law of the Sea treaty.

However, in the mineral-rich and deep coasts of Japan, the country is working to bring research seabed mining operations to a commercial scale by 2024 for strategically important rare earth minerals. In the case of international waters, the High Seas Treaty signed among U.N. members in March exempts deep-sea mining from environmental impact assessment (EIA) measures.

International Seabed Authority, or ISA, has entered into 15-year exploration contracts for polymetallic nodules (PMN), polymetallic sulphides (PMS) and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (CFC) in the deep seabed with 22 contractors. Among them, The Metals Company, anticipates several projects will go into commercial-scale production by the end of 2024.

The ISA's drawn out process on finalizing the mining code — the lynchpin to delaying commercial production — was accelerated when Nauru, a small South Pacific island nation, invoked a two-year rule in the Law of the Sea treaty. This provision mandated the ISA to complete the mining code by July 9, 2023, or accept mining applications in its absence, further strengthening the drive towards commercial deep sea mining.

“The International Seabed Authority has been mandated to regulate this activity and put in place the exploration and the exploitation regulations while protecting the marine environment," The Metals Company CEO Gerard Barron told MINING.COM. "The NGOs have been trying to use the legal method to oppose deep sea mining, to perpetuate a delay. How badly they’ve got it wrong.”

When MINING.COM reporter Bruno Venditti asked Barron about the 13 nations calling for a moratorium on deep sea mining, Barron concluded, “this is all just noise. Even the nations that are resistant, like France and Germany, have been working very hard over the last weeks to progress the code."

At the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada conference in March, Investing News Network's Charlotte McLeod noted the high-cost, high-risk mining industry as a whole is suffering from a lack of capital. For steel manufacturers, this is a problem, as nickel and manganese supply chains are at times strained and over-subscribed.

When it comes to securing funds for the capital expenditures necessary for ramping up mining, partnering with mining majors, turning to royalty stream companies and partnering with manufacturers offer miners options. Underground operations do often benefit from having a high (if hard to reach) ore body grade as well.

High grades above ground are few and far between, and can be in remote and undeveloped areas. As technology develops, anchoring and strip mining the seabed for minerals may prove to be a more nimble method. It's also challenging from a remediation perspective.

"'No net loss' in biodiversity is not achievable through remediation and offset," scientists wrote in a Frontiers in Marine Science article discussing remediation options and challenges for the sea floor. "Experiments typically show that it takes decades after the disturbance for signs of recovery to be observed in deep-sea ecosystems, and if faunal abundance does recover, the species that colonise can be different to those that were there previously."

Additionally, the high costs associated with restoration in the deep sea could significantly hinder its feasibility, writes the lead author Daphne Cuvelier of Instituto do MAR and Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre in Horta, Portugal.

Barron told MINING.COM both automakers and steelmaking companies are interested in his company, despite a moratorium signed by Renault-Nissan, Samsung, Volvo and others. Notable non-signatories include GM, Tesla and several major battery companies.