Ocean Fungi: Nature's New Plastic-Eating Superheroes

Team now investigating whether these remarkable fungi can tackle even tougher plastics

Source: Ronja Steinbach, University of Hawai'i

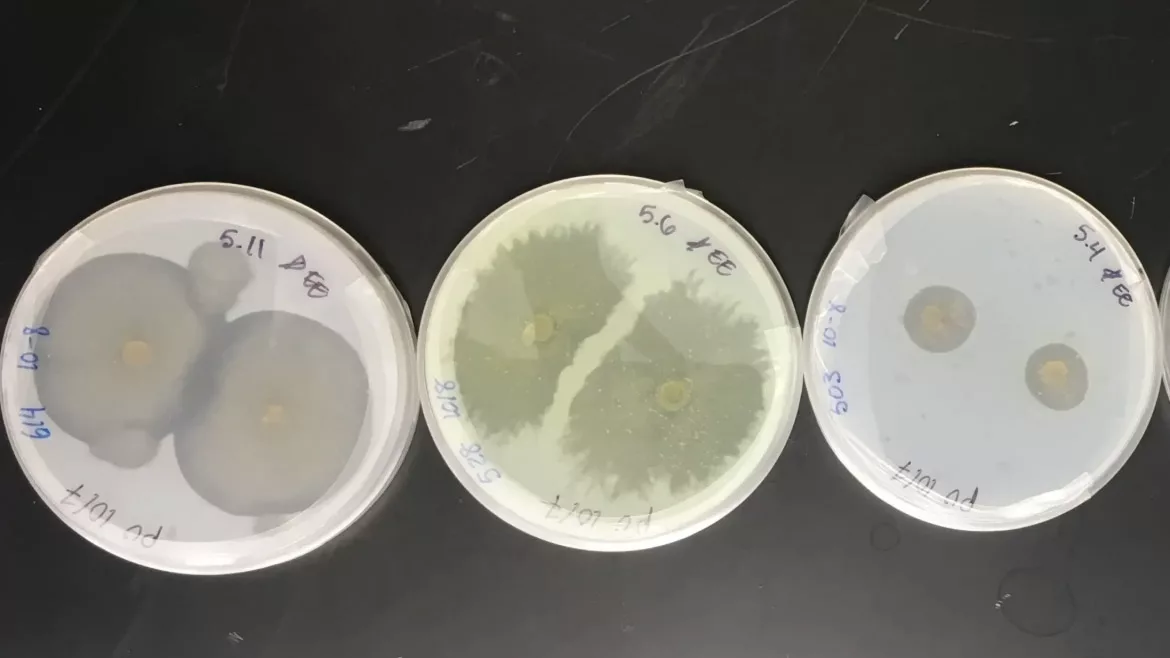

In a discovery that could help tackle one of our planet's most pressing environmental challenges, researchers at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa have found that many marine fungi can break down plastic – and they can be trained to do it faster.

The study, published in Mycologia, reveals that over 60% of fungi collected from Hawai'i's coastal waters demonstrated the ability to degrade polyurethane, a common plastic used in various industrial and medical products.

"Plastic in the environment today is extremely long-lived, and is nearly impossible to degrade using existing technologies," said Ronja Steinbach, who led the research as an undergraduate student at UH Mānoa's College of Natural Sciences. "Our research highlights marine fungi as a promising and largely untapped group to investigate for new ways to recycle and remove plastic from nature."

The discovery comes at a crucial time. Each year, the equivalent of 625,000 garbage trucks worth of plastic enters our oceans, creating devastating environmental impacts. This plastic doesn't simply decompose – instead, it breaks down into dangerous microplastics that can harm marine life and concentrate toxic chemicals.

What makes these fungi particularly special is their adaptability. Through experimental evolution, the research team found that some fungi could increase their plastic-consuming abilities by up to 15% in just three months of exposure to the material.

"Fungi possess a superpower for eating things that other organisms can't digest," explained Anthony Amend, a professor at the Pacific Biosciences Research Center who supervised the research. His team collected fungi from various marine sources, including sand, seaweed, corals, and sponges around O'ahu.

The location of this research is particularly significant. Hawai'i sits within the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, near the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch, making it a natural laboratory for studying plastic pollution solutions.

The UH Mānoa team isn't stopping here. They're now investigating whether these remarkable fungi can tackle even tougher plastics, such as polyethylene and polyethylene terephthalate – materials that represent an even larger portion of marine pollution. They're also working to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind this plastic-degrading ability.

"We hope to collaborate with engineers, chemists, and oceanographers who can leverage these findings into actual solutions to clean up our beaches and oceans," Steinbach concluded, pointing toward a future where nature's own recyclers might help solve one of humanity's biggest environmental challenges.

.webp?height=200&t=1674043769&width=200)